Click here to get “Young Turks” on Vudu.

Tag Archives: Patt Morrison

Young Turks Now Available on iTunes

Click here to see “Young Turks” on iTunes.

Click here to see “Young Turks” on iTunes.

Young Turks Out on Cable and Digital Dec. 17

Indie Rights is pleased to announce the Dec. 17 release of “Young Turks” on cable video on demand (including Comcast, Cox, Frontier and Verizon FIOS) and digital platforms (iTunes, XBox, Playstation and Vudu).

Indie Rights is pleased to announce the Dec. 17 release of “Young Turks” on cable video on demand (including Comcast, Cox, Frontier and Verizon FIOS) and digital platforms (iTunes, XBox, Playstation and Vudu).

Hunter Drohojowska-Philp, author of “Rebels in Paradise: The Los Angeles Art Scene and the 1960s” and “Full Bloom: The Art and Life of Georgia O’Keeffe, wrote that “Young Turks” was a “kaleidoscopic melange of bizarre underground existence and a few naked truths.”

For more information, please call Linda Nelson of Indie Rights at 213/613-1587 or email her at info@nelsonmadisonfilms.com

Downtown Blues

Linda Frye Burnham’s “Downtown Blues,” with guitar work by Jimmy Townes, is the unofficial anthem of “Young Turks,” to be released on cable, iTunes and other digital platforms on Dec. 17.

Using a lot of unseen footage from the outtakes of the movie, editor Pamela Wilson has put together a music video to Burnham’s recording of the song, which was produced by the Dark Bob.

Young Turks on Cable, iTunes Dec. 17

Indie Rights has announced that “Young Turks” will be distributed nationwide on cable, iTunes and other digital platforms on Dec. 17, 2013.

Indie Rights has announced that “Young Turks” will be distributed nationwide on cable, iTunes and other digital platforms on Dec. 17, 2013.

Coleen Sterritt to Exhibit New Works

Another Year in LA will present Torque, an exhibition of recent sculpture and works on paper by Los Angeles artist Coleen Sterritt. Sterritt, one of the “Young Turks,” uses old doors, household fixtures, masking tape, milled lumber, furniture and building materials to create abstract compositions with strong polarities — forms that have a compelling resonance while being familiar and unknown at the same time. Her works on paper incorporate geometric and organic forms, and refer to both man-made and natural forms and structures.

Critic Peter Frank wrote about Sterritt’s work, “You never quite know what’s going to happen with/in/at a Sterritt structure —except that, for all its piling-on of discrete units, it’s going to balance, against all odds, with an entirely unlikely dignity.”

The raw materials and basic DIY quality of her wall tableau “And Then Some” upsets the original use of its components, yet none has been skewed so radically that it is not immediately recognizable. When hung on the wall, they form a sculptural haiku.

Collectively, the sculpture in Torque appears as if it is the residue of the perfect storm, a still point (neither still nor in motion) amidst a tsunami of chaos and material excess.

Coleen Sterritt: TorqueRecent Sculpture and Works on Paper

November 14, 2013 – January 3, 2014

Opening Reception: Thursday, November 14, 5-8 PM

another year in LA

Pacific Design Center, Suite B267

8687 Melrose

West Hollywood, CA 90069

Gallery phone: (323)223-4000

www.anotheryearinla.com

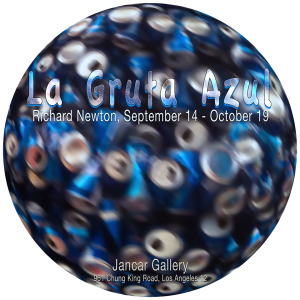

The Times Reviews La Gruta Azul

Great write-up by the Los Angeles Times’ Christopher Knight for Richard Newton’s installation, “La Gruta Azul,” at Jancar Gallery in Chinatown.

Great write-up by the Los Angeles Times’ Christopher Knight for Richard Newton’s installation, “La Gruta Azul,” at Jancar Gallery in Chinatown.

With this work, writes Knight, “Newton commemorates shattering loss” in an installation that is “surprisingly refined and even elegant, given the throwaway materials.”

Read the whole review here.

Jancar Gallery961 Chung King Road

Chinatown

(213) 625-2522

Through Oct. 19

Closed Sunday through Tuesday For more information on Richard Newton, visit his website here. “Young Turks” is out on DVD and will soon be available for download and viewing on iTunes and other digital platforms.

Richard Newton: The Missing Turk

When Stephen Seemayer projected a rough cut of “Young Turks” against a downtown warehouse wall in 1981, Richard Newton was not among the artists included in the film.

When Stephen Seemayer projected a rough cut of “Young Turks” against a downtown warehouse wall in 1981, Richard Newton was not among the artists included in the film.

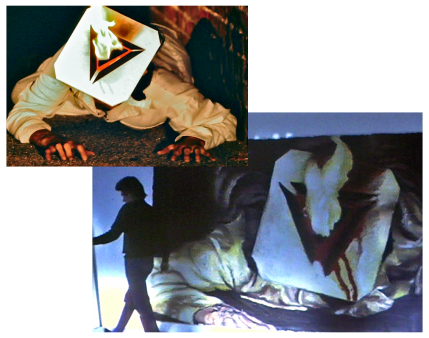

Seemayer and Newton had been very good friends and collaborators on several videos — including “A Glancing Blow” (see excerpt below), in which Seemayer was a cameraman in one of the cars. Seemayer had filmed Newton doing performances and talking about his work, just as he had the other downtown artists that he was friends with in those days. Seemayer had even assemble-edited Newton’s section of the film, which included Newton taking viewers on “the first tour” of the as-yet-unbuilt Museum of Contemporary Art on Bunker Hill.

But for one reason or another — the two friends still cannot agree on what went wrong — Seemayer left Newton’s footage on the cutting room floor when he put together the first rough cut for the 1981 screening.

When Seemayer and editor Pamela Wilson decided to reenvision “Young Turks” in 2012, they agreed the section was worth reviving and added it back into the finished film.

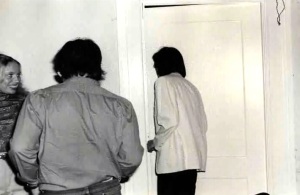

In “Young Turks,” Newton explains some of the ideas behind his performances of the late 1970s and early 1980s, in which he inhabited hotel rooms for an extended period and the audience observed through cracked doors and windows what he was doing inside.

Audience members view Newton’s 1980 performance through a door in the Hotel El Dorado on Spring Street.

“If we’re artists,” Newton explains, “we might think that, somehow, we’re doing something special that’s different from what the rest of the people are doing, either the people working, or the people just living on the street.

“But in fact, we’re doing kind of the same thing. We’re in a pattern. We make our art, we go through certain rituals. We have certain things we have to do to survive.”

Inside the hotel room, Newton conversed with his stuffed animal “friends” while getting progressively more drunk.

In “Get Under the Table, Don’t Look at the Windows” — a 1980 performance at the Hotel El Dorado on Spring Street — Newton inhabited a room of what was then a rundown flophouse and explored alcoholism and fears of nuclear annihilation in conversations with stuffed animals that were observed by the audience through a crack in the room’s chain-secured door.

“When I’m in that room,” Newton says in “Young Turks,” “the kind of activity I’m involved in is the same kind activity that a child would be involved in, that an adult who’s living in that hotel would be involved in, and that an artist would be involved in, staying in their own studio and working on their own.”

Newton has never ceased making art. He continues to create films and performances, and his latest work, “La Gruta Azul” (“The Blue Grotto”) — an installation at Jancar Gallery in Chinatown — will open on Saturday, Sept. 14, 2013. The opening reception will be from 6-9 p.m. at the gallery at 961 Chung King Road, Los Angeles 90012. The exhibit runs through October 19.

Newton has never ceased making art. He continues to create films and performances, and his latest work, “La Gruta Azul” (“The Blue Grotto”) — an installation at Jancar Gallery in Chinatown — will open on Saturday, Sept. 14, 2013. The opening reception will be from 6-9 p.m. at the gallery at 961 Chung King Road, Los Angeles 90012. The exhibit runs through October 19.

Andy Wilf: Troubled Genius

By PAMELA WILSON

When he was sober, Andy Wilf was a thoughtful, funny, productive painter with unlimited potential for artistic achievement and acclaim. When he wasn’t, he became reckless, dangerous and destructive.

When he was sober, Andy Wilf was a thoughtful, funny, productive painter with unlimited potential for artistic achievement and acclaim. When he wasn’t, he became reckless, dangerous and destructive.

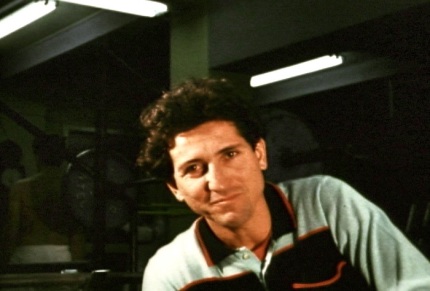

This Jekyll and Hyde schism is boldly illustrated in “Young Turks.”

In the documentary — which was filmed in Downtown L.A. between 1977 and 1981 — Wilf is handsome and smiling at a table in front of one of his latest canvases. He eloquently tells artist and filmmaker Stephen Seemayer about the progression of his work from photorealism to expressionism.

In the documentary — which was filmed in Downtown L.A. between 1977 and 1981 — Wilf is handsome and smiling at a table in front of one of his latest canvases. He eloquently tells artist and filmmaker Stephen Seemayer about the progression of his work from photorealism to expressionism.

“I was incorporating different materials into the paint,” he explains, “looking for something to change the manipulation, to make it less maneuverable, to make it new again for me.”

Intercut with this articulate interview are asides directed straight into the camera in which Wilf agonizes numbly over his substance abuse and futile attempts at rehabilitation.

Intercut with this articulate interview are asides directed straight into the camera in which Wilf agonizes numbly over his substance abuse and futile attempts at rehabilitation.

“I took 50 valiums at 5 milligrams today…” he intones, “and they don’t want me to go to Schick Center, and they want me to pay 8,000 dollars, and I want my sodium pentathol…”

Wilf, who was born and raised in the Los Angeles area, then tells Seemayer of an artist-in-residence gig he landed in 1979 at a university in Yuma, Arizona. “I thought that would kind of help get me squared away, to get away,” he says.

But that attempt to get “squared away” backfired in spectacular fashion, ending in a three-day binge of drinking, abandoning his classes and doing drugs that culminated with Wilf’s dismissal by the university’s dean. In a rage, Wilf threatened the dean, threw a chair through a window and ended up in jail.

“But that isn’t like me at all,” Wilf tells Seemayer in “Young Turks.” “It was because of … all the other chemicals that was [at] maximum input in there. My brain was pretty well out to lunch.”

The heartbreaking truth for Wilf’s friends and admirers was that, despite numerous attempts to overcome his addiction, Wilf was doomed to lose the battle. “His paintings were personal exorcisms,” wrote art critic Hunter Drohojowska in a 1982 issue of L.A. Weekly, “catalogues of his determined ritual of self-destruction.”

The heartbreaking truth for Wilf’s friends and admirers was that, despite numerous attempts to overcome his addiction, Wilf was doomed to lose the battle. “His paintings were personal exorcisms,” wrote art critic Hunter Drohojowska in a 1982 issue of L.A. Weekly, “catalogues of his determined ritual of self-destruction.”

Andy Wilf died at 32 of an accidental drug overdose in January 1982, just a few months after the rough cut of “Young Turks” was screened.

If his personality was divided, his body of work was solid. After Wilf’s death, artist Roger Herman told Suzanne Muchnic of the L.A. Times, “He functioned so well on drugs, he didn’t take them to get high, he took them to avoid depression.”

Born Aug. 25, 1949, to Mormon parents in Lynwood, Wilf showed an aptitude for drawing as a young child, an impulse encouraged by his mother, Lucille, who had studied painting at UCLA. He started his art career after high school, working at a factory in Compton that churned out motel-room paintings on a production line.

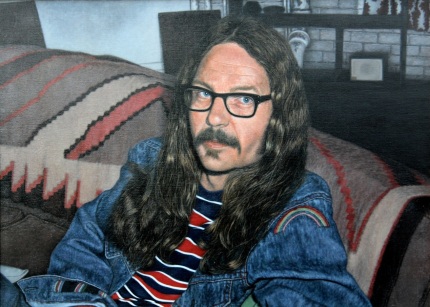

“Portrait of John Schroeder” (1975), acrylic on canvas. Collection of Susanne Dorschel, Wiesbaden, Germany.

In 1972, he started using photographs as the basis for his work, which evolved into photorealist portraiture. His “Portrait of John Schroeder” (1975) is a study in exactitude. As Muchnic wrote of Wilf’s photorealist works in 1983, “These paintings of long-haired young men and middle-aged people with leathery faces confront the viewer, their ordinary appearances scrupulously observed by the camera’s unflinching eye.”

By 1978, when he and his wife, Carey Kawaye, had moved into the Victor Clothing building at 240 S. Broadway, Wilf’s style had begun to loosen up a bit. The larger space of his downtown loft allowed him to use bigger and bigger canvases. “Just like the goldfish kind of thing,” Wilf says in “Young Turks,” “bigger bowl, they grow.”

Living next door to Linda Frye Burnham, he also gained access to photographs being sent in to her High Performance magazine, such as those of Hermann Nitsch and Barbara Smith, which Wilf translated into huge paintings with graphic overtones of violence and death.

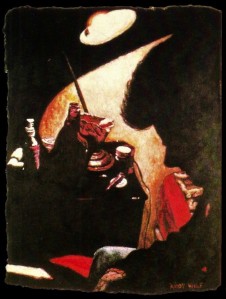

Canvases such as “Burning Desire,” an interpretation of Seemayer’s performance behind a mask on fire, and “Bound Figure,” in which Rudolf Schwarzkogler’s prone body is shrouded in strips of gauzy cloth, depict “cropped, large, terrifying figures, easily readable but with painterly surfaces,” Muchnic wrote.

Canvases such as “Burning Desire,” an interpretation of Seemayer’s performance behind a mask on fire, and “Bound Figure,” in which Rudolf Schwarzkogler’s prone body is shrouded in strips of gauzy cloth, depict “cropped, large, terrifying figures, easily readable but with painterly surfaces,” Muchnic wrote.

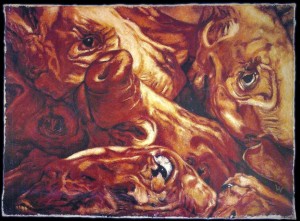

Wilf’s expressionism reached its zenith with a series of paintings inspired by the butcher shops of Grand Central Market, across the street from his downtown loft. In paintings such as “Dead Ends,” lifeless eyes in bloody piles of pig snouts and calves’ heads stare at the viewer with both astonishment and accusation. As Patt Morrison of The Times wrote in an obituary of Wilf in 1982, these are “choice cuts sliced out and the offal tossed aside, a metaphor for the castoffs of human greed.”

Wilf’s expressionism reached its zenith with a series of paintings inspired by the butcher shops of Grand Central Market, across the street from his downtown loft. In paintings such as “Dead Ends,” lifeless eyes in bloody piles of pig snouts and calves’ heads stare at the viewer with both astonishment and accusation. As Patt Morrison of The Times wrote in an obituary of Wilf in 1982, these are “choice cuts sliced out and the offal tossed aside, a metaphor for the castoffs of human greed.”

“Dead Ends” was shown in 1983 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, which two years earlier had honored Wilf with the Young Talent Purchase Award. In a program for the 1983 exhibit of Wilf’s work at LACMA, curator Maurice Tuchman wrote of the awards ceremony, “When his name was announced at the prize reception, tumultuous applause broke out among the scores of artists present. In the degree of its intensity, this response, virtually unprecedented in my experience, both reflected the artist’s own volatile and highly emotional nature and clearly revealed his charismatic effect on others.”

In her appreciation after his death, Muchnic reported that, “Wilf later confided to friends that he took the $3,000 awarded him and ‘shot it up my arm.’ “

In her appreciation after his death, Muchnic reported that, “Wilf later confided to friends that he took the $3,000 awarded him and ‘shot it up my arm.’ “

For his last painting, as Morrison wrote in the Times obit, “Andrew Wilf painted something else he saw — himself, as a shadow figure sitting at a drug-strewn table. ‘Peace Through Chemistry,’ he had entitled it.”

Artist Fails in Self-Exorcism, LA Times, Jan 20, 1982 Last Exit From a Living Hell, LA Times, Jan 21, 1982